Abattoir

Part Two: Pigs and Sheep

An addition to my historical dairy farming year project.

Although some practices have altered since I followed an agricultural year through in 1980

and concluded it with three months photographing at an abattoir (see Part One),

much of what I saw then hasn’t changed in essence.

I still believe that British farming sets a fine example to the rest of the world

with its high standards of livestock husbandry and slaughter.

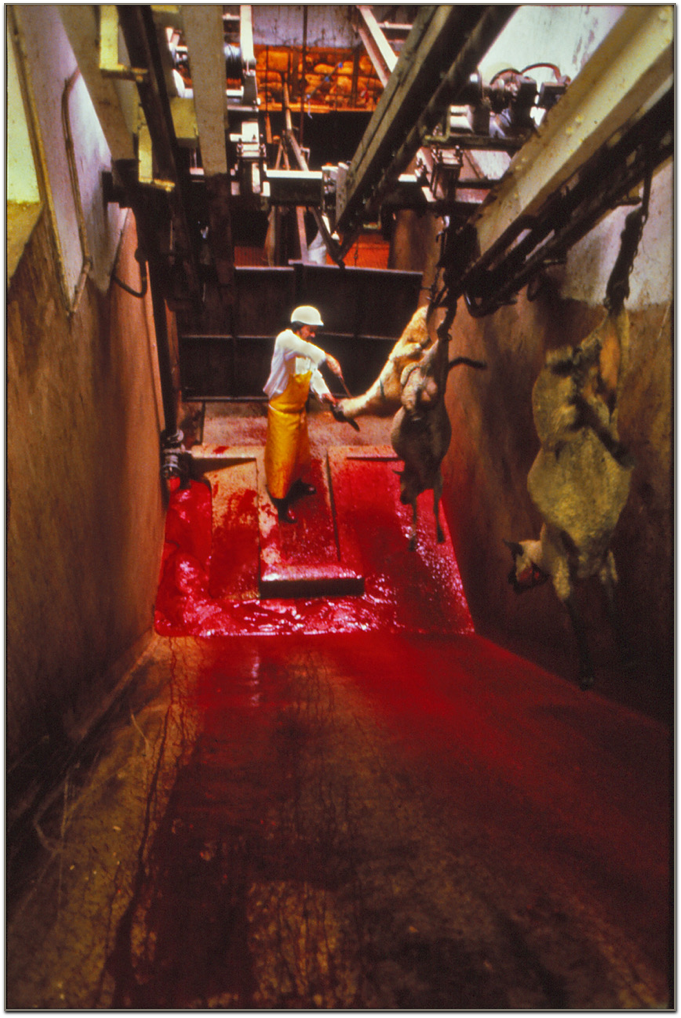

At the FMC abattoir in Exeter in 1980, cattle, pigs and sheep were all slaughtered and dressed under the same roof. Since then, legislation prompted by BSE and Foot and Mouth has mostly changed that practice. Specialist pig abattoirs using ‘controlled atmosphere killing’ (gassing) are replacing the type of stunning - electric current applied with electrodes - shown here. Argon and nitrogen are asphyxiants said to cause no pain, whereas carbon dioxide is toxic and is highly controversial. Perhaps there is something to be said for the older method, but mass production sways current practice. After slaughter, modern principles are similar to the past.

Piglets and sheep could be dealt with in groups but fully grown ‘porkers’ were tackled alone. The senior slaughterman admitted to me that he found despatching pigs difficult. They were intelligent. They were the nearest animals in appearance and sensitivity to humans. And they were strong and therefore potentially dangerous. He treated them with respect

Hosing quietened them. Perhaps it was soothing. The slaughtermen said that

it dampened their spirits and made them easier to handle.

Would-be escapees evaded capture only to find themselves stranded in an even worse place.

I struggled to continue with the project after this, although it was an isolated incident.

Pig carcasses are hoisted onto pulleys and exsanguinated (throats cut to drain blood), then taken by conveyor belt (like the sheep pictured below) to the butchering floor above. Here they are scalded in hot water to soften their bristles, before being scraped clean in a tumbler.

After bristle removal, carcasses are split into two categories for dressing. Bacon comes from

small pigs which are relatively easy to handle, in a production line similar to sheep. ‘Porkers’

are dressed like cattle - gutted and then mechanically sawn down the middle into two sides.

The cleaning ritual is endlessly performed until the end of the line is reached, and then some.

Public health inspection follows.

A Public Health Inspector gives the all important stamp of approval.

Finished meat is weighed and labelled, then moved back downstairs again for cold storage.

Here it either awaits collection by its owners or nationwide distribution from the lorry bay

Meanwhile, another production line carries on.

Sheep

Like a lamb to the slaughter, so the saying goes.

On my initial tour of the abattoir, I was told that the number of sheep being slaughtered is governed by seasonal demand. ‘Summer is the peak,’ a manager told me as we stood in the yard before going into the factory, ‘especially here in the South West of England where an influx of tourists increases the market for lamb chops. And by the way,’ he said smiling but perfectly serious, ‘all sheep become lamb. Do not, under any circumstances, refer to sheep carcasses as mutton.’

Here is a guide to nomenclature. It all comes down to teeth. Lamb must be under twelve months of age with no permanent incisor wear. Hogget is from yearlings with no more than two worn incisors. Mutton is from female sheep (ewes) or castrated males (wethers) of two years age or more, with a least two worn incisors.

I was given the complete freedom to see everything, as long as it was reported fairly. I’ve tried.

*

A captive bolt pistol is used to stun sheep prior to slaughtering

the traditional English way, with a vertical slash to the throat.

Moslem halal slaughter of the live animal is preceded by electrical stunning.

Slaughter is by ritual horizontal throat cut

Sheep are stunned, slaughtered and bled in clusters of three. Then a conveyor belt transports them

to the butchering floor above. Cleaning occupies the lull before the next batch comes through.

The production line overhead is in full swing, butchering and

dressing the slaughtered sheep to transform them into lamb.

Fleeces are peeled off and cut free.

By-product fleeces are jettisoned downstairs through chutes before messy innards are exposed.

Unwanted innards wend their way downstairs - then out through the back door

Remember how teeth differentiate between lamb and mutton?

Well - after decapitation, mutton could quite easily be dressed as lamb.

And down the hatch goes the waste, as well as by-products.

Meanwhile the carcass is stripped of internal organs requiring public health inspection.

And then washed.

Inspected, weighed and labelled.

Cold-stored or awaiting collection in the loading bay. The finished product. Lamb.

Am I still a Meat Eater?

So now that ‘Abattoir’ is done, it’s time for me to think again about becoming vegetarian - that’s only fair after encouraging other people to consider what being a meat eater entails, by looking at this project.

Perhaps I was too dispassionate forty years ago, cut off from reality by my camera lens. But I had a job to do and was trying to be scrupulously fair. Maybe I should have been less professional and more humanitarian. It could have made me give up eating meat. But that’s history. What about now?

During my recent research, I was surprised to see how little in principle had changed. That reassured me, finding what I had to say was still relevant. But I was amazed at the sheer scale of operations now - and appalled by the mass killing of pigs through carbon dioxide gassing, a horrible way to die. There are other gases which could be used that are not toxic. I for one am happy to pay more for pork put to sleep before slaughter, not poisoned, as I am for lamb which is not halal. I will not knowingly eat meat killed by either of these two methods. I regard them both as cruel.

In conclusion, my appetite for meat has certainly wained since doing this project. Fish and veg and sweet things do appeal to me far more than a rare steak or a bloody lamb chop. I couldn’t eat either of those items now. They have become repulsive to me. But I can still enjoy meat in a casserole, or chew my way through small portions of well done (incinerated!) cuts or slices. It’s a compromise, but it enables me to fit in with the lifestyle that my family and most of my friends enjoy. For now.

*