Here are extracts from two of my photo-books. They combine an introductory text, images and

captions to tell their stories. Both are factually based and semi-autobiographical.

My Great War Story

This is my story: of five summers spent on the Western Front, when I was a young woman. My companion was a man thirty two years older than me, the Surrealist artist and Fantasy Press poetry publisher and printer, Oscar Mellor, whom I later married. Both of us were fascinated by WW1, from my childhood to his grave.

On The Somme, it was always summer for me. Five summers, wandering the open farm land, bleached soil and dusty, each day’s exploration relieved by lunch served from the boot of our car in the fields. French stick, broken crusts smoothed by artisan butter, with red wine in a vin de table beaker. I remember savouring all of it on one special day, in the sheltered hollow where an artillery gun emplacement had been. It could have been led by my grandfather, a career soldier in the Royal Artillery. Arthur Henry Virgin, or was it Henry Arthur Virgin, I was never sure. He fathered twins named after him: Arthur being the first by a minute could indicate A H Virgin, but who knows? The war changed him. The young soldier who rose to sergeant in the Raj in India and then RSM in Ypres and on the Somme, became wholly private again back in Blighty.

Mum said he never spoke about his time in The Great War, but she blamed it for his smouldering moods and angry beatings of her mother, bounced around the kitchen, wall by wall. I wondered how many other old soldiers were the same, never speaking, just re-enacting the war with a wife as punch-bag.

Visitors were scarce, forty years ago, when I began visiting the French sector of the Western Front. The war widows who besieged it during the 1920s were long gone: they came asking questions and searching for answers - where were their missing men? But all they found were ruins. They left and never returned, leaving the Western Front to finally became "All Quiet".

Oscar and I raised French eyebrows when our British number plate was spotted, despite being camouflaged in a native Renault car. But when we emerged, an old man with a young woman - oh la la! Brits were rare. I only recall meeting one other English visitor on the battlefields or in the cemeteries, a war historian with a memorable name, Dr Stan Snowball.

I also remember meeting only one British war veteran, at the Schwaben Redoubt on the Somme. He was very small, a tunneller, and very quiet. There must have been more, but they were all silent too, invisible in the company of ghosts.

In Flanders, like The Somme, we were also invariably the only British visitors. But there, by contrast, local people made us welcome. They were grateful for the soldiers’ sacrifices in their defence. We were befriended by a young family who lived near Hyde Park Corner cemetery; in their cool, tile floored, oasis of a house, we were given beer and lunch. We discussed the war’s influence on the Ypres they grew up in, and exchanged Christmas cards each passing year.

In Messines, on a hot lonely Sunday with the village shuttered down, we were surprised to find the Town Hall door ajar. Inside in the gloom we found an enormous desk. Behind that desk sat a small man. He grinned. Rising from his chair, he enthusiastically shook our hands and introduced himself as George, the Mayor of Messines. His English was poor and our Flemish non-existent, so he beckoned us to follow him outside, into the sunshine, then into our cars.

We drove along a winding country lane, until suddenly we stopped and had to stand in the middle of the road. George pointed to a white demarcation line and announced "In Belgium we piss on France”. Oscar, ever the Francophile, smiled nervously, but me? I fell in love with Flanders that day.

I always felt comfortable around Ypres, and uneasy on The Somme. The fields and woods that I wandered endlessly around, however, were dangerous underfoot in both places. In the tiny Kroonart trench museum we shared gossip with the curator, a gentle man who showed us his haphazard jumble of artefacts. We heard how a young farmer’s son had recently lost his legs. He drove his tractor ploughshare over a shell which detonated. It blew his tractor and his body apart, claiming another victim for a war which still continued maiming and killing, sixty years after its armistice.

In a corner of each farmer’s fields lay shells in nests of twisted shrapnel, collected after every Autumn ‘s ploughing season, when the earth heaved up and ousted battlefield relics. So rich was this harvest that much was left where it emerged. I would scan the freshly ploughed earth to find handfuls of 303 rifle cases and bullets, plus wadges of five abreast cartridges. Sometimes there were bones, left to become dust.

In one seemingly barren field, I kicked around lumps of mud, until Oscar shouted “Stop! Look at what you’re treading on.” The mud lumps were Mills bombs; heavily ribbed hand grenades, the size of goose eggs, with detonators intact. I looked curiously at them, tempted to touch, but he hurried me away.

Once, I found many bones, clustered amongst ruined bunkers by Zillebecke Lake near Ypres.

Should I leave them, I wondered, bury them perhaps, leave them lost without trace forever? Or should their anonymity be recognised under a white stone, formally interred as an unknown “Soldier of the Great War”? We decided to take them to the office of The Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

I was puzzled by the reaction that our arrival with the bones provoked. We were not Field Archaeologists, just visitors who had found something by accident. I had expected to simply hand the bones over with a note of where they had come from - five minutes, then go. Instead, we were told that we must return immediately to the place where the remains had been found, escorted by a Commissioner, and show him exactly where they had lain.

We drove in silence back to Zillebecke and clambered into the concrete slabbed and iron rodded ruins of a bunker. The Commissioner was dressed for the office, dark suited and shiny shoed. The silence was broken by a deep sigh, before the real reason for the journey was revealed. Murder. Victims were often dumped in these killing fields, anonymous in the safety of numbers. This was the perfect killer’s burial ground. It was a police requirement that finds such as our bones had to be investigated. So, we were assisting in a police investigation! Dusting off his shoes, it was made clear that the Commissioner found this and us, a damned nuisance.

I wonder how many more naïve visitors like us have knocked at the Commission’s door since? I hope most finds are left where they were found, not pocketed as souvenirs!

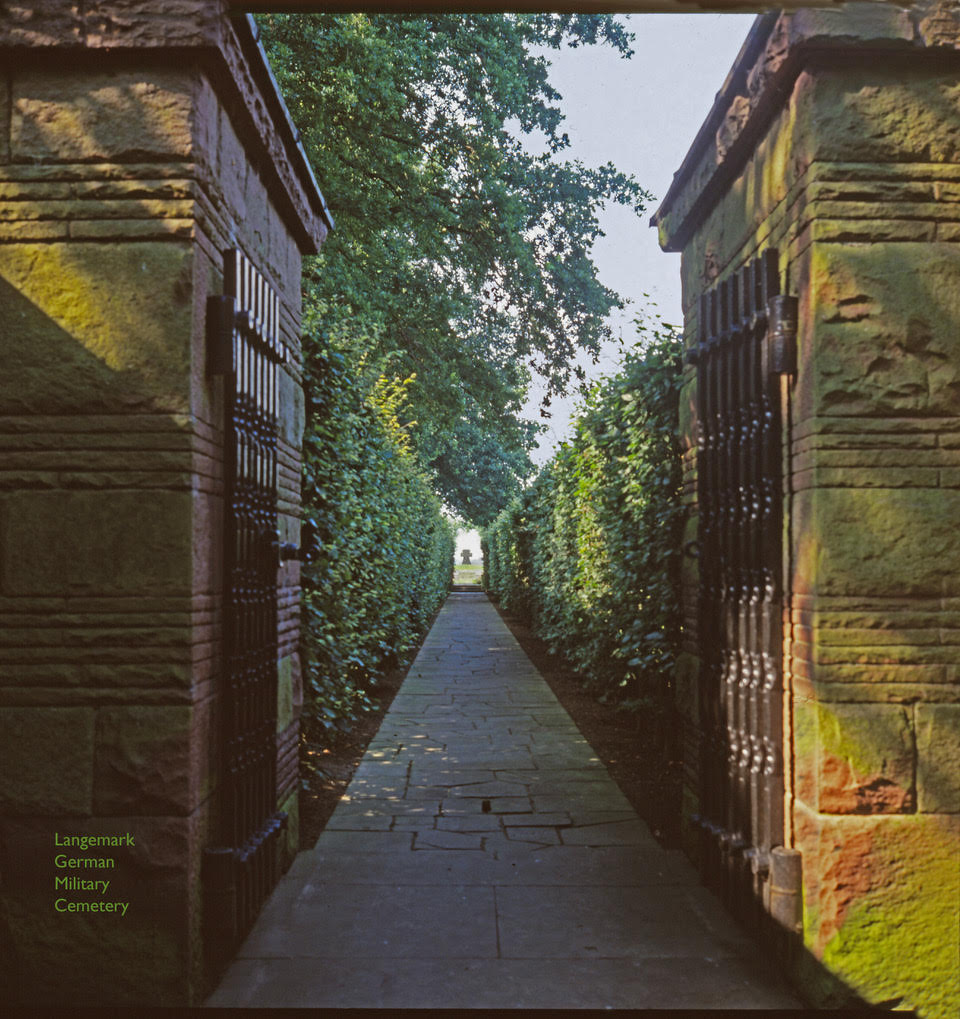

Sixty years after the war had ended, German cemeteries and indeed German visitors were still shunned by the local population. All Second Reich soldiers had been rounded up by the French and Belgian authorities and reburied in just five cemeteries. These were sited around mass graves which could not be moved. They had no gardens to gentle death, unlike the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s cemeteries. No red rose bushes, no shining white stones, just dark crucifixes or heavy Teutonic crosses on grass amongst trees. I wondered if they were deliberately oppressive, in perpetual revenge for the German invasion?

It was the stark simplicity of the dark crosses at Neuville St Vlast German Cemetery, running in endless lines, that brought home the desolation of war to me. Looking closer, there were four soldiers embraced by most graves. Company in death was much needed in this cold hard place -except it seems for the Jews, who were buried alone. Strangely, their distinctive headstones were left untouched by the Nazis during the Third Reich.

This Concentration of Graves took place just after the Great War had finished. To those involved in the work, it must have seemed as though hostilities were never ending. Soldiers of all nationalities were exhumed from their original burial sites (which were scattered and often undocumented) to be reburied in formal cemeteries. It was a huge and necessary task, but another horror of the war, haunting all who witnessed it. I hope that some eventually returned to the battlefields, perhaps many years later as elderly veterans, to find that wonderful sense of peace which I found in the Commonwealth cemeteries.

*

From 1979 to 1984, I spent most of each summer on the Western Front in Northern France and Belgium, but my fascination with WW1 began much earlier, when I was a child. Our tiny family TV screen in its oversized wooden box showed "The Great War" film series, narrated by Laurence Olivier. It was overpowering. My mother shunned us as my father and I wept. That flickering screen made history come alive and emotions run deep; so when I grew up, I had to go to the Western Front and tread its broken earth, to confront my childhood memories.

A hundred years have passed since my grandfather, RSM Virgin, served on the Western Front, and almost forty since I last trod those battlefields. I wondered if the Centenary was a good time for me to return, so I searched the internet to catch up with places which I knew and loved. Sadly, I discovered that most had been trampled almost out of recognition by thousands of visitors. Battlefield tours run by commercial guides were destroying the very things that everyone wanted to see.

Looking at present day Sanctuary Wood near Ypres on the net, I noticed that its original war detritus was gone and its trenches ground down into virtual oblivion by an army of tourists.

Nearby, Hill 60’s perfectly preserved German bunker still looked pristine, but all around it, houses encroached. I read of the local families with nowhere to live and of land hungry developers.

My pictures portray the Western Front in a time before tourists trampled the trenches smooth. Impromptu field museums were still dusty Aladdin’s caves, not sterile under glass, with "Do Not Touch" hanging heavy in the air. There was much to see and little disturbance to what remained. Searching on the internet today, only the tranquil cemeteries and some of the memorial parks look unspoilt.

On the Somme, I saw farmers’ fields edging up against the fiercely fought over Glory Hole. Even the British owned Lochnager mine crater, bought to preserve its enormity for all time, looked demeaned. It stood alone, separated from related sites. Sad, because it was among a series of mines blown after continuous bombardment stopped and silence fell, before the attack on 1st July 1916, the First Day of The Somme.

Modern life is swamping what remains, burying it under concrete and brick, sealed by tourists’ feet.

But I will return. One day.

My Great War Story pictures with commentary

A battlefield tour of some evocative places on the Western Front.